The greater the man, the greater the quantity of universe he contains

Tancredi Parmeggiani

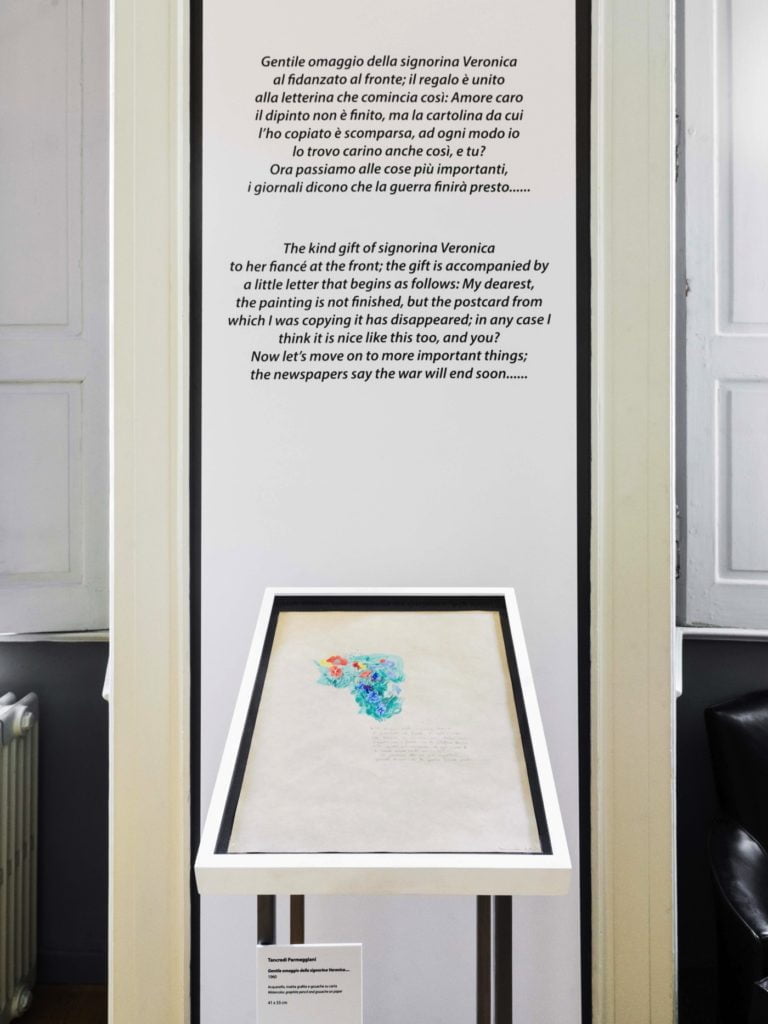

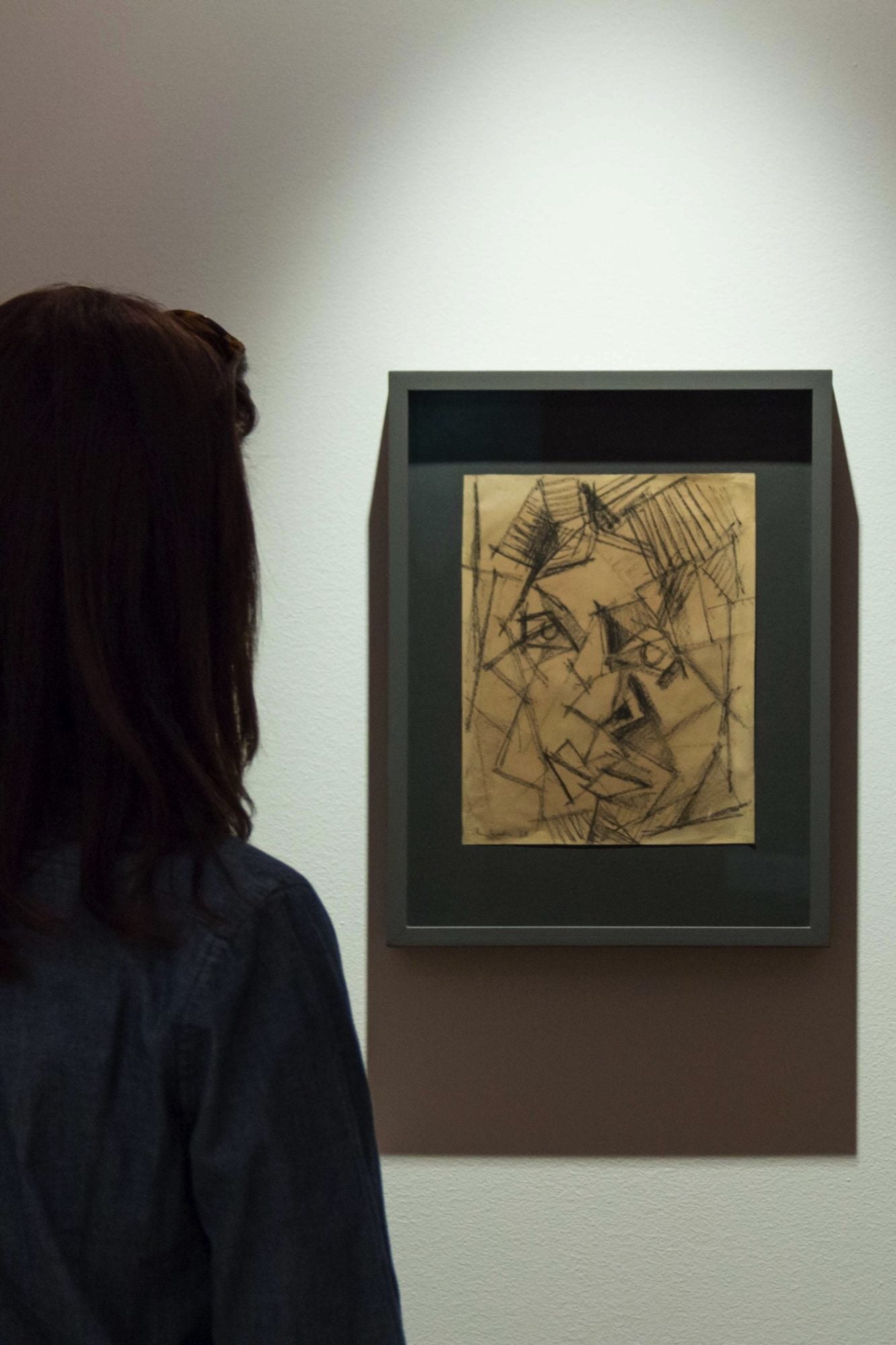

This exhibition by Collezione Ramo -Italian 20th-Century Drawing- focuses on the artist Tancredi (Feltre 1927 – Rome 1964), chosen as an emblematic fgure among the 110 artists included in the collection’s overview. The show has been developed in collaboration with Alessandro Parmeggiani, who has loaned several works from the artist’s collection available for the event. Two factors make Tancredi a paradigmatic fgure in this context. First of all, the fact that all his output was marked by an emphasis on the importance of drawing. His works on paper have never been shown in all their originality and variety, either in exhibitions or in exhaustive publications, as if they were less important than his paintings. Yet for Tancredi drawing was always an impelling, everyday expressive necessity, ever since childhood. His very many works on paper, made in a wide range of techniques (tempera, gouache, pastels, watercolors, graphite, ink) are never preparatory studies for paintings. The drawing stands out with the force of independence from his painted works, like a parallel world of great intimacy, stemming from the need to free his mind of nightmares and restrictions, and at the same time from a pursuit of lightness. The freedom of the drawing is also the result of the very rare ability Tancredi possessed to visualize the complex spatial structure of his paintings as he was making them. For the artist, drawing was an ongoing conversation with himself, in which the eye thought and the hand expressed itself on paper. On a sheet of paper (which was an inexpensive material) Tancredi could let himself be transported by the creatures that appeared in his mind, fxing them on the surface, liberating them and liberating himself. The second reason that led to the choice of Tancredi is his capacity to cross diferent movements of the last century, absorbing them and making them his own, always in restless pursuit of new advances in experimentation. The documentation of the various expressive phases of an artist is precisely one of the characteristic features of Collezione Ramo, created with a didactic spirit, beyond market logic. The fact that Tancredi was able to foreshadow certain trends made him at times incomprehensible for his contemporaries, just as his changes of style made him difcult to recognize for a superfcial gaze. In spite of the fact that his production can be ascribed to a period of just 15 years (from 1949, the year of his frst solo show in a gallery, to 1964, the year of his death), daring originality was a constant in his output. Tancredi never set out to please the market, relying on a particular style, even if it was widely appreciated; instead, he was always driven by profound intellectual honesty, but pursuit of improvement of himself and the society through faith in an artistic contribution that would be authentically free. His drawing, of course, followed his changes of style, above all in the last years of his life during which his production on paper increased enormously with respect to the previous decade, because (Tancredi states this clearly in his writing) the dealers had insisted that he paint, forcing him to neglect the exercise of drawing. The exhibition, then, concentrates on the moment after the artist’s abandonment of the Informale, from 1960 to 1964, to document the changes of style of those years, in which drawing seems to ofer him, more than ever before, a shelter from the malaise of life. A passage from the abstract to the fgurative is documented by two large works in ink, never shown elsewhere, in which slender geometric forms defne a feld of action with elegance, and the spiral enhances the spatial depth. Later, the production focuses on the series of Facezie (Witticisms), fgures that inhabit the space, at times arriving from afar, from the depths of childhood experience, while others are based on social events, as in “Le pose della Callas” (The Poses of Maria Callas). The Facezie are always “fgured emotional impressions” (Tancredi defned the witticism as “a jest made with a bit of lightness and a touch of bitterness” and come prior to the passage to the descriptive realism of the last months of the artist’s life, documented here by two self-portraits with the gaze lost in the void, beyond the white surface of the paper or canvas. Between these two moments there are several works that tell the story of another Tancredi, ironic and humorous, an aspect of his character that has remained alive in the memories of those who knew him. Two works in particular deserve comment. One represents a bouquet of fowers and is accompanied by a text written by the artist who identifes with a hypothetical fancée of a soldier at the front, to whom he sends a bouquet of fowers drawn with love, a gift of beauty and nature to get past the brutality of the war. The other work is entitled “La Critica” (Criticism and also the critic) on the back, and in an almost comic-book tone features a bare tree, to the upper left, from which emerges a parade of naked fgures that in couples menacingly face of, crossing the page from left to right. In the foreground, a beautiful, shapely woman advances, with an air of superiority, holding a fower in her right hand and a brush she brings to her hair in the left hand. Here is the critic (“La Critica”), as in the title. Comparing the drawing to its reproductions from years ago, we see that Tancredi had glued seven little leaves over the privates of some of the characters, which today, 47 years later, have come unstuck, leaving rough signs on the paper. The little leaves seen in an old catalogue now document Tancredi jesting intervention, where he applied them to the nude fgures just as the Church had dictated in the past, ever since the antique paintings of Adam and Eve. An indispensable thank you should be extended to Alessandro Parmeggiani, Tancredi’s son, who has with great enthusiasm loaned the works on paper which his uncle Luigi Scatturin conserved in the archives of the Parmeggiani heirs in Venice until 1997, works that then passed to his mother Tove in Oslo, where they are still conserved by Tancredi’s children (Alessandro and Elisabet). Alessandro has not only permitted the display of some works never shown before and others that had not been exhibited for decades but he has also taken vigorous part in the basic idea behind Collezione Ramo, that of assigning value and dignity to drawing, on a par with painting. Tancredi on paper still awaits discovery, to a great extent, and this exhibition sets out to stimulate further study.